Black Marlin vs Blue Marlin Differences

How they’re alike, how they’re different

Before we even explore the physical and situational differences between a blue and black marlin, we need to understand that the circumstances in which we engage these creatures can be far different from the species themselves. Environmental factors such as sea conditions, geographical location and/or the presence of predators can have a huge influence on marlin behavior, as well as how we drive on them once hooked. ¶ Tackle size, hook type, and the intention to boat or release the fish will also affect fish behavior on the wire, and how we react to that behavior with the boat. With that said, these two awesome beasts do indeed exhibit some consistent behavioral traits that also differ quite considerably from one another.

If I had only one word to separate blue marlin from black marlin, that word would be speed. A big blue’s first run can test tackle to the limits and drastically reduce the odds of the fish either successfully being boated or released in good health.

The belly created by allowing hundreds of yards of line to disappear off the reel during the initial run can create a situation similar to starting on your own 1-yard line with your heels on the goal line. Sometimes this scenario is unavoidable, but there are a few ways to manage the situation right off the bat.

Let’s say we are pulling lures on 130-pound tackle, and the left long gets piled on by one over 800 pounds and starts ripping line off the reel. I like to have the crew pull down the halyards on the fish side of the spread to bring the lines closer to the waterline. This allows me to turn the boat toward the fish and reduce the speed at which we are losing line. We will be able to keep fishing on the opposite side while the fish side is being cleared, and if necessary, I can increase the boat’s speed to keep up with the fish.

Another slightly more aggressive option in the same scenario would be to back straight past your spread, allowing the baits to clear the stern by having them swim in front of the boat. Once the inside dredge is cleared, the crew can clear the spread that is now in front of the boat, away from the fish. At this point, you might have some confused and concerned anglers and crew if they haven’t seen this tactic before, especially if it wasn’t discussed ahead of time.

The fish side should always be cleared first so the boat can be spun around to chase the fish with the pointy end—which is always safer and usually more productive—while the nonfish side of the spread is cleared. For me, sea conditions and trolling direction relative to the wave direction will dictate which option to use at the time to avoid backing up-sea if possible.

Both of these options have worked well to combat a blue marlin’s speed on its initial run, and a few times we’ve lost half a spool no matter what we tried. Managing the initial loss of line on lighter tackle is no less important, but the turn-and-chase option gets a little more precarious as the closer to parallel to the fish you need to be to avoid the drag slipping on the belly in the line. Two-, 4- and sometimes 6-pound-test main line can break on the belly simply due to the friction caused by the speed at which the fish is swimming against the water’s pressure. Maybe this is one reason why the 2-pound-line-class blue marlin world record is vacant in the Atlantic and Pacific for both men and women, while the men’s and women’s black marlin 2-pound-line-class world records have been weighed. This doesn’t mean by any stretch of the imagination that black marlin are pushovers, but it might suggest that a blue marlin’s speed is superior to the black’s.

To back up this claim, I asked longtime record fisherman Capt. Trevor Cockle to weigh in on the topic. Cockle ran the famed The Madam and The Hooker mothership operation for 17 years and was part of 75 world records on all species of billfish, using everything from 2-pound-test to fly to heavy 130-pound tackle.

“A blue marlin will typically make a long initial run, often combined with a series of jumps. If you don’t catch them in that short window after they are winded from airing out on the surface, they will typically try to go deep on you. You need a lot of patience when this happens, and it is best to stay off the fish and allow them to come up when they tire of the conditions down deep. In some areas of the world, oxygen is lacking at deeper depths, which can lead to pulling up a dead marlin if the captain sits on top of the fish during the fight—turning it into a straight-up-and-down pulling contest. If you stay off the fish, be patient and use technique; the outcome is usually a more successful one. As much fun as it is chasing an insane blue one in reverse, there is both a time and a place for it,” Cockle says.

The locations we target blue marlin around the globe tend to have certain things in common as well. We typically find blues in water that ranges between 70 and 85 degrees, with larger fish able to tolerate cooler water for longer periods of time. We have raised fish in water below 70 degrees in Madeira, but our best fishing was in water from 72 to 75 degrees. Bait, current and bottom structure play huge roles in concentrating populations of blue marlin. Areas where steady ocean currents push up from deep water against seamounts, edges or islands can hold a wide variety of bait, which in turn will attract all manner of pelagic species to feed on as they pass by on their migratory routes. These tiny specks on the map can produce some incredible blue marlin fishing during some years, while other years can be a complete bust if the bait doesn’t show or the fish get pushed slightly off course by the current.

It can be extremely frustrating when the targeted species doesn’t get the memo about when and where to show up, but that is the risk you take when you try to track down these incredible animals. However, when they do show up to your chosen speck on the map, you’d better hang on.

It is well-known that black marlin have fixed pectoral fins that don’t retract and lie flat like the blue’s, but they also have shorter, thicker bills and a dorsal fin that is less than half the size of the fish’s total body height compared with the dorsal on a blue, which is approximately two-thirds the height of the body. The full-grown version of a black marlin tends to be bulkier in the head and shoulders, which is instantly apparent when one climbs onto your skipbait

A black marlin’s speed might be just one notch below a blue’s, but what they might lack in speed, they certainly make up for in strength. Once one gets her head down and digs in, it can be extremely difficult to get the big girl to move. Changing angles, varying the reel drag, and pulling the leader across the fish’s back can be effective in getting both species to change direction, but, in my opinion, when a big black goes down and stays calm, it can make an angler second-guess just how much fun they are actually having.

Thirty to 40 minutes of 45 pounds of drag can wear down even the fittest angler, especially when they see the fish come up jumping as if she doesn’t even notice the drag weight. This seems especially true with a big girl that has already given you a shot at the leader and felt the extra weight of the wireman, and makes another run away from the boat. Generally speaking, it seems that even giant black marlin will give you a shot at the leader in first 10 to 20 minutes of the fight. This makes for some incredible footage on the leader because they tend to jump more up than out, which allows the crewman to hold on to the leader through the whole show.

Blue marlin put on some incredible shows around the boat also, but in my opinion, nothing compares to an 800-pound black airing out on the leader a dozen times 10 feet from the transom, with the crewman still holding on and the boat keeping pace with every jump. They are truly a crowd-pleaser during the endgame, and anglers from all over the world happily go to Cairns, Australia—the epicenter of black marlin fishing—every year to see it. If this place is not on your bucket list, it should be.

Tim Dean is the captain of the 47-foot O’Brian Calypso, who fishes up and down the east coast of Australia from Bermagui to Lizard Island, chasing blue, black and striped marlin. Dean has decades of experience fighting fish of all sizes on all sizes of tackle, from fly gear to 130-pound conventional. Whenever fighting a big black on heavy tackle, Dean says that there is certainly an emphasis on the use of angles and pressure: “Something we really rely on with the big ones is the use of drag and patience.” He goes on to say that “sitting on top of the fish with the boat is a mistake,” and that doing so will turn the fight into a pulling contest that you will lose nine times out of 10. “We tend to sit back a bit creating angles and using drag—heavy drag—to agitate the fish to the surface, giving you the jump-set that you need to get the gaff or tag shot.”

Blacks are more stable in the water due to their fixed pec fins, but they are infinitely more structured in their movements than blues, and they pull hard on the leader and jump when they are messed with. “I find that it is a two-man job on the deck with blacks on the Great Barrier Reef,” Dean says, “and watching each other’s backs when the jumping starts is imperative to be sure the man on the leader is clear behind him with respect to the leader, and to make sure the angler is following correct drag use and procedures. As for the tug of war, I think the black marlin wins that battle. As for crazy? The blue marlin wins crazy—hands down.”

“One important factor when discussing the differences between these two majestic creatures is the depth of water in which each are typically found,” Cockle says. “The blues are usually found in 100 fathoms or deeper, as opposed to the blacks, which are typically located in 50 fathoms or even less. The difference in water depth between the two normally sets the stage for how to fight the fish.”

The depth of water that black marlin typically inhabit can be a definite advantage to the captain, and that water depth absolutely plays a role when fighting a fish. Using the shallower water, the boat can change pulling angles much quicker and with a more immediate effect on the fish. Cockle recalls a specific instance where he used the shallow water and the maneuverability of the little G&S The Hooker to confuse and frustrate a black marlin: “We hooked a nice black in Panama years ago in 300 feet of water. I had a lot of fun on light tackle with that fish, cutting it off from going into the deeper surrounding water column. We played that game for a while until she got so frustrated that she began to jump all over the place, which allowed us to close the deal just minutes later on very light line class.”

We typically target these fish in much shallower water than blues, and with less importance placed on water clarity and color. Areas of broken ground, rock piles surrounded by flats, and coral-reef systems that hold varieties of baitfish can be target-rich environments for chasing blacks, especially when bait is present in large quantities.

The Zane Grey Reef just outside Piñas Bay, Panama, is an area that holds bait in large quantities, to say the least. While the name suggests that the ZGR is a vast area of bottom structure, it is, in reality, a rather small rock pile coming up from about 300 feet with a few small satellite peaks looming in the flats that surround it. The Zane Grey Reef is tiny when compared with the Great Barrier Reef—which is without a doubt the undisputed champion of bottom structure—but what the ZGR lacks in total square footage, it makes up for with some incredibly concentrated surface and subsurface bait activity. When the conditions are right, acres of bonito, rainbow runners and small yellowfin tuna can be seen busting on the surface, and occasionally being scattered by a hungry black marlin pushing through the school. Blacks will pile up in a tight area like this, and when the switch goes on, they will tear through schools of bait—until the switch goes off. On the ZGR, it’s pretty easy to tell when the switch is on by watching the dozen or so 31-foot Bertrams belonging to the Tropic Star Lodge backing around at the same time.

No matter which species you target, one thing is certain: You are in for one hell of an adventure. Whether it’s watching the mono crack off your 130 at an alarming rate, or a sea monster airing out right next to the boat, these fish will leave a mark on all who are lucky enough to experience it.

Watching professionals like Dean and Cockle work these fish is a learning opportunity in itself for all those on board. Some of my best memories were made while working the deck for these two guys, and I am absolutely certain that other great captains out there have done the same for their anglers and crew. Moments like these are what keep us chasing marlin to the far reaches of the globe, hoping we hit it right, with each of the variables coming together to make for one epic season.

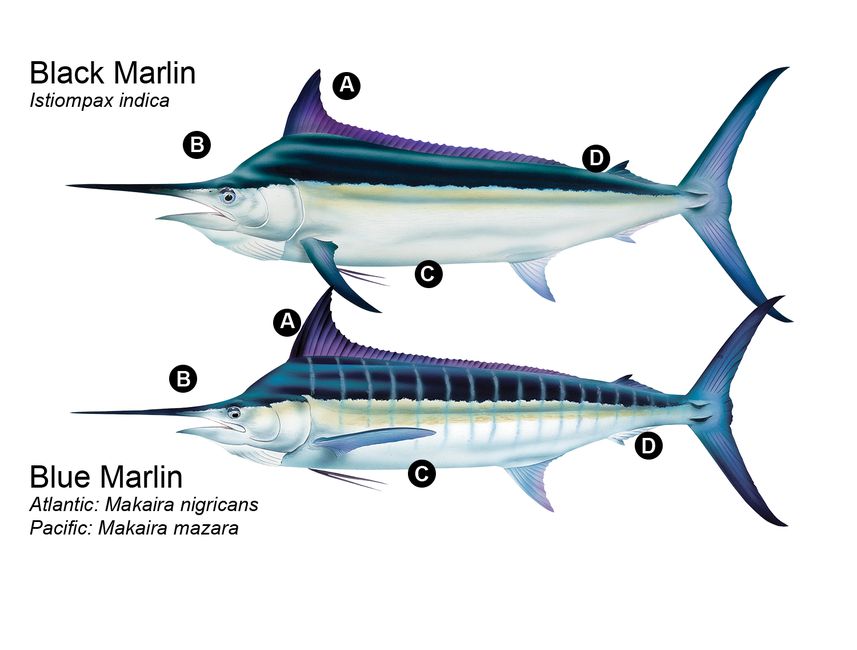

A: Dorsal Fin: A black marlin’s dorsal fin is approximately one-third the height of the fish’s body; by comparison, a blue marlin’s dorsal is much taller, over half its body height.

B: Bill and Head: Black marlin are thicker in the head, with a slightly shorter bill; in larger fish, the bill might have a slight downturn. Blue marlin are a bit more streamlined, with a longer, more slender bill.

C: Pectoral Fins: A black’s pectoral fins are fixed and rigid, unable to fold against the body, while a blue marlin’s pec fins fold easily against the fish’s sides, perhaps contributing to its acrobatic ability.

D: Coloration: Black marlin are predominantly very dark blue above the lateral line, quickly fading to hues of green or gold, then to shades of silver or white below. Blacks can display faint-blue vertical stripes, while a blue marlin’s coloration is often vividly blue with shades of purple, frequently with iridescent-blue vertical stripes running the length of the body.

Article Courtesy Marlin Magazine

[post-carousel-pro id=”5407″]

You May Also Like:

How and where to catch trophy roosterfish

Roosterfish a fish to crow about

How to catch tuna in Costa Rica

How to identify billfish species

Join our mailing list

[yikes-mailchimp form=”1″]

The sight of a big marlin airing out so close to the Great Barrier Reef is one that anglers from around the world dream about.

The sight of a big marlin airing out so close to the Great Barrier Reef is one that anglers from around the world dream about.