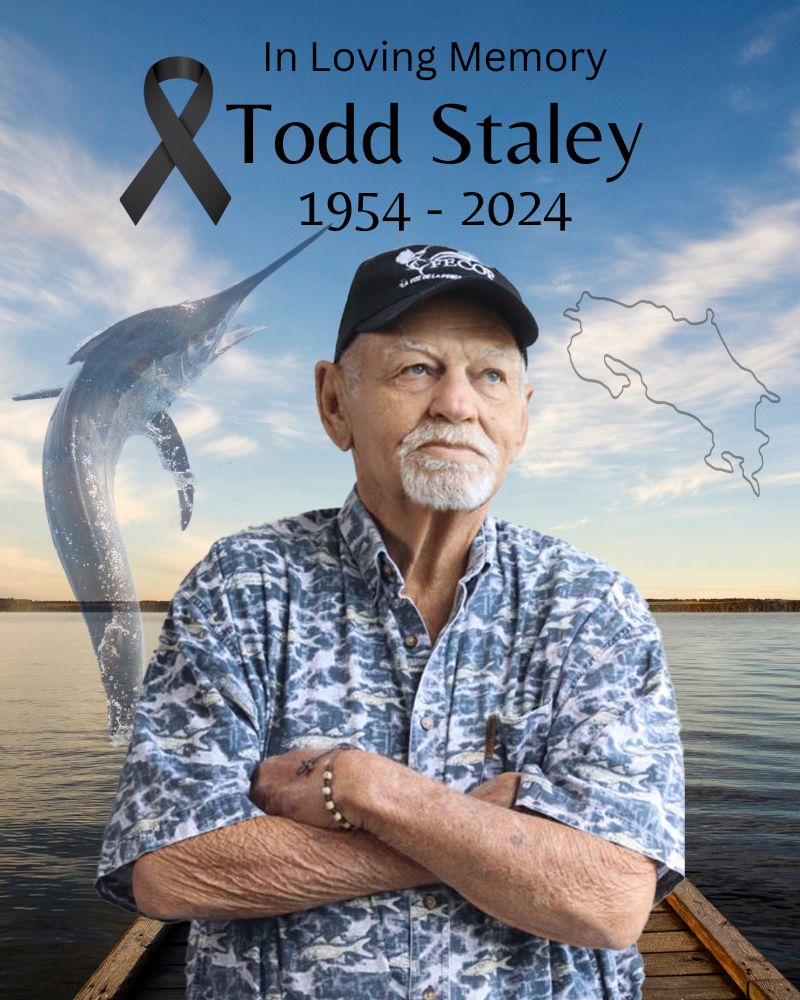

Young Biologist Studies Sailfish in Costa Rica

The sailfish popped up in the spread lit up in an iridescent purple hue. This fish was hungry and vigorously slashed the teaser with its bill. Everyone jumped into action. Capt. Melvin Sánchez sounded the alarm from the tower, as he was the first to see the oceanic swordsman appear. Mate Sharlye Oporta screamed for the angler to get ready, and the angler reached for his 14-weight fly rod attached to a fly that looked like half of a pink chicken with a hook in. Beatriz Naranjo anxiously observed.

It had been a frustrating morning. This was the fifth fish that had showed up in the spread, the array of teasers (lures without hooks) trolled behind the boat to attract billfish (marlin and sailfish). The angler, a visitor to Costa Rica from Colorado, was a well-versed fly fisherman when it came to small fish, streams and much lighter equipment. He had often read of the exciting battles with large deep-sea creatures on a fly rod, and it was on his bucket list.

the air.

The first fish was a case of buck fever. The teasers were cleared, the fish took the fly and the angler froze. In half a second the sailfish figured this wasn’t as tasty as it thought and spit it out.

The first fish was a case of buck fever. The teasers were cleared, the fish took the fly and the angler froze. In half a second the sailfish figured this wasn’t as tasty as it thought and spit it out.

In the second attempt the back cast ended wrapped up in the outrigger and the opportunity was lost. Fish number three, the angler tried to set the hook with his rod instead of pulling on the line, and the fish escaped. The next fish came in lazy and wasn’t interested.

Now fish number five came up hot. Everyone did a quick little “fish” prayer in their head. No one on board wanted to see that fish caught more than Beatriz Naranjo.

When some little girls were playing with dolls, playing make-believe hairdresser or make-believe mom, Beatriz was exploring the forest near her home in Tarrazú, high up in coffee country. She and her cousins would spend all day climbing trees, walking creek beds and turning over whatever they could move to see what lived underneath. It is little wonder she chose to study science, specifically marine science, at the University of Costa Rica, from which she graduated.

When FECOP (the Costa Rica Sport fishing Federation) teamed up with Gray Taxidermy’s fish tagging research program, they put their heads together to reward college students interested in studying species related to sportfishing. That encompasses not only pelagic species, but many inshore species also. They decided to have a competition among students from all universities in Costa Rica, and Beatriz won a scholarship with her proposal to study the feeding ecology of sport fish.

That science has had many advancements. Beatriz became interested in feeding ecology while studying the stomach contents of rainbow trout in the high altitudes of the Savegre River. That required killing the sample and opening the stomach. It also told the story of a very short window of time in the animal’s life. Today, with a very small tissue sample from a live animal, scientists can determine what exactly that fish has been feeding on over a long period of time.

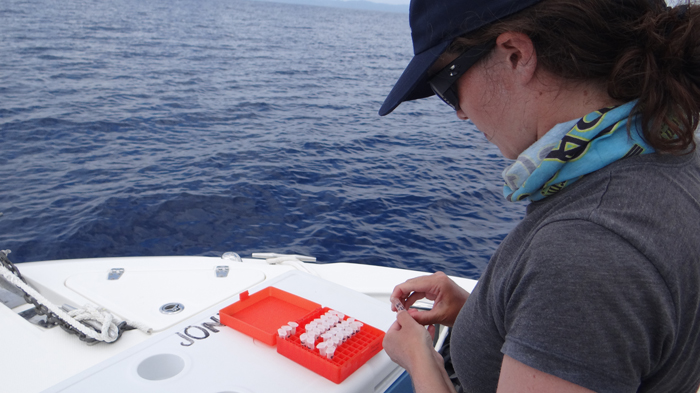

For inshore species such as snappers, groupers, congrias, and mackerel, she could seek the assistance of artisanal fishermen for samples. For species that are normal catch-and-release, she needed to ride along on sport fishing boats. She has gathered nearly 800 samples, which co-scholarship winner José Luis Molina will soon be studying in a laboratory.

FECOP’s director of science and research, Moises Mug, says the partnership with Gray FishTag Research has been a win-win for all.

“Their database is growing rapidly, at rates that have surpassed the NOAA tagging programs, so NOAA is now partnering with Gray FishTag Research to improve their own tagging program,” he said. “Also, in addition to tagging all species that our professional charter boat captains and customers seek in Costa Rica, they have successfully deployed satellite tagging for the first time ever on a roosterfish in Costa Rica.”

Beatriz, who did most of her pelagic studies out of Puerto Jiménez, liked the area so much she has settled there and works as a guide for Aventuras Tropicales kayak tours, often doing long treks in the Golfo Dulce. After graduation in June, she plans to pursue a master’s in scientific nature and do a study on mercury levels in Costa Rican fish.

“Before I got involved in this study I did not like sport fishing,” Beatriz said. “It has had a bad reputation among Costa Rican people. What I met was very nice people, families and couples who come to our country to fish.”

What impressed her most were the Costa Ricans who worked on the boats and how they cared for the fish that they caught and released. Many told her they used to be commercial fisherman and were away from their families for weeks at a time. Now they make a better living and are home with their families every night.

And so now sailfish number five charged in. Teasers were cleared and the angler from Colorado made his cast. This time, when the fish engulfed the fly, the angler didn’t flinch. He set the hook with a slip-strike, pulling on the line instead of the rod, and instantly the fish burned 150 yards of line off the reel and began its dance across the flat blue aquatic dance floor.

Thirty minutes later the fish was beside the boat and Beatriz jumped into action. She placed a tag in the fish to study its movements and took a small sample of tissue before releasing it. The angler high-fived his crew as he scratched one off the bucket list.

These studies will become invaluable in learning more about, and responsibly managing, billfish. I personally am very interested to see what they feed on over a long period of time – besides half a pink chicken.